The Role of Chronemics and Proxemics in Communication - 3Rd Issue

"For negotiations or meetings, it is always wise to lure others into your territory, or the territory of your choice. You have your bearings, while they see nothing familiar and are subtly placed on the defensive."

- Robert Greene, The 48 Laws of Power -

***

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the third issue of "Oddities & Curiosities", Mudita's "no-frills", irregular newsletter.

As anticipated in the previous issue, the new course on Time Management is now online (preview available here) and – given the strong links between time orientation and territoriality – it will soon be followed by a course on Space Management.

How do the concepts of "space" and "territoriality" affect workplace behaviour?

For starters:

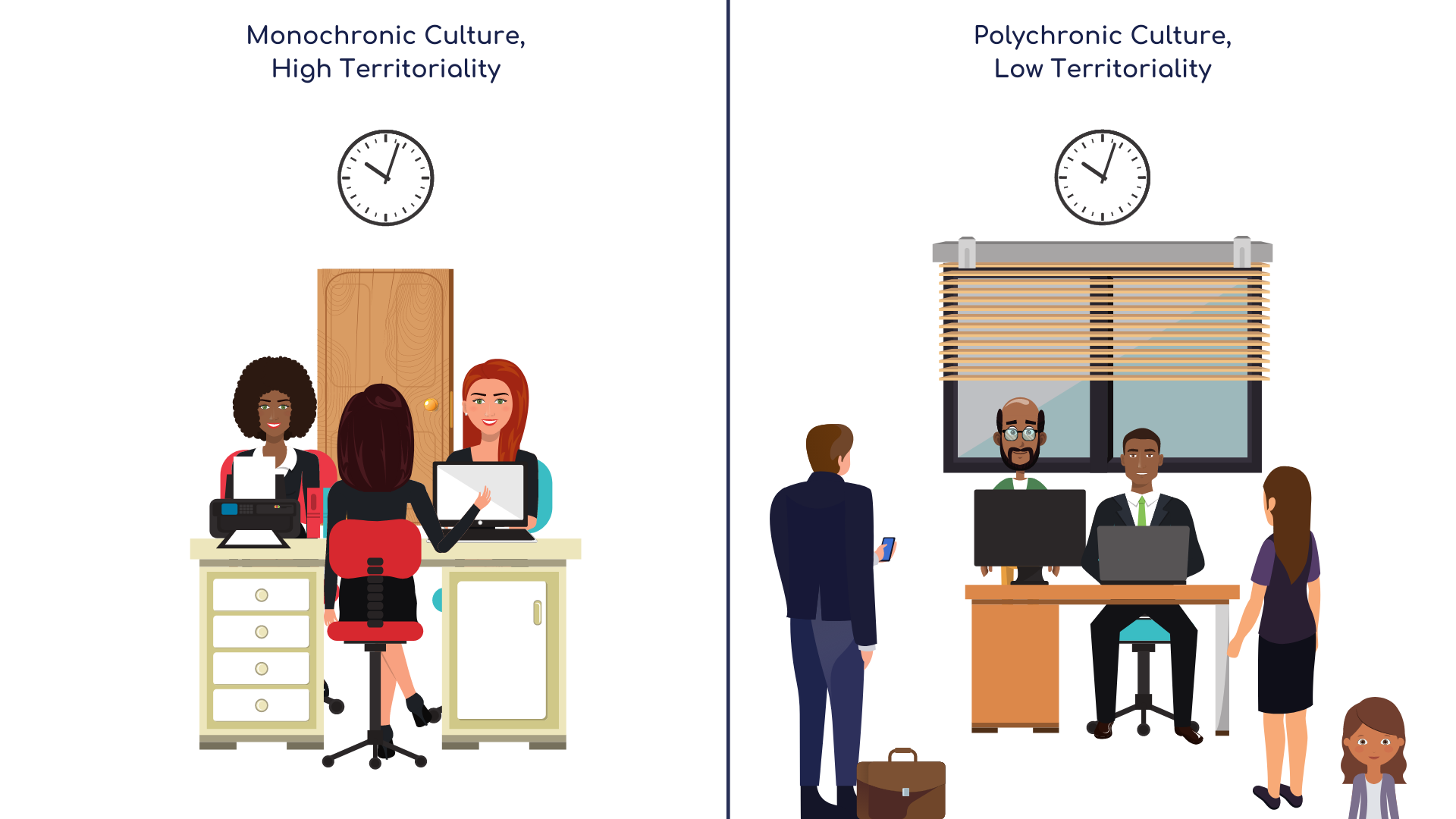

- monochrons are greatly concerned with privacy, ownership, don't respond particularly well to personal closeness, and are not very tolerant of interruptions. When people in monochronic societies don’t have time for someone, "time becomes a room which some people are allowed to enter, while others are excluded". (E.T. Hall);

- polychrons, on the other hand, have a low sense of ownership of both space and material belongings, which they are usually happy to share with others. Polychronic societies emphasize the importance of social relationships over tasks: being slightly late for a meeting is more acceptable than disrupting an ongoing conversation.

What else? What other links are there between time (chronemics) and space (proxemics) management?

Both chronemics and proxemics are heavily influenced by power dynamics, and concerned with dominance and status:

- "One who is in the position to cause another to wait has power over him. To be kept waiting is to imply that one's time is less valuable than that of the one who imposes the wait." (Guerrero, DeVito & Hecht);

- "By the same token, occupying higher positions usually means being introduced to a bigger desk and a larger office. In extreme situations top officials occupy vast rooms which symbolize nothing more but status. As stated by the authors of Discourses in Place, ‘all of the signs and symbols take a major part of their meaning from how and where they are placed’. And this is predominantly the major territorial communication in our times – the bigger space occupied by you and your belongings, the more important, influential and rich you must be." (Sobocinski)

On a related note, in the upcoming article – that will serve as an introduction to the course on Space Management – we’ll explore the implications of power dynamics in the virtual workplace:

- "Many of us are sheltering-in-place, practicing social solidarity by physically distancing, and shifting to majority online work and organizing in midst of the global coronavirus pandemic. For many folks that means adjusting to different work spaces and work-flows, ones where virtual meetings have become a regular and expected activity. On the one hand, being able to work from home or participate in virtual meetings represents a very clear form of privilege, in that you have work to do and don’t have to do it in higher-risk settings like caregiving and essential retail. But within our online meeting spaces, other forms of privilege and associated power dynamics play out in ways that undermine our work and marginalize important voices and perspectives.

What are some ways that people have power and privilege in virtual meetings?

- […] Designated work space: people who have a designated quiet, private, well-lit space where they can connect, those who have a house, bedroom, home office to work from and concentrate within." (Arellano)

- "Space can be considered as a resource, and thus control over space and a greater ability to use it for attaining one's goals can be a major benefit. Therefore, we should systematically study the social and psychological impacts of not only the amount of area per person but also differential control over space. This readily brings to mind the fact that people of low status (e.g. the urban poor, the child in the crowded household) may have less of a claim to space when it is in high demand than do people of high status (the urban affluent, adults in the home). Therefore, it would be important to examine the differential impact of dense conditions on those with high status vs those with low status. Actual power over spatial use should minimize overload and allow one to conduct desired activities with less interference, while less power would lead to more interruptions and the inability to conduct preferred activities. Studies of control and crowding should thus concentrate on differences between those within collectivities who have more or less social power in their everyday environments." (Baldassarre)

***

To be notified about the publication of new material on Space Management, please subscribe to "Oddities & Curiosities".

Thank you (as always!) for your time and support,

Maria

Despina Moralidou is a chartered linguist (CIOL) and accredited translator, and for the better part of her adult life she has been working as a freelance translator/editor and in-house project manager specializing in Web, Marketing and Software localization. She has a Master’s degree in Specialized Translation (Surrey) and a Postgraduate diploma in International Cultural Cooperation & Management (Barcelona). She sometimes writes and/or shares thoughts on language, culture, her field of work, and anything else that catches her eye here .